Obreros: Jonathan Molina-Garcia

(b. 1989) Jonathan Molina-Garcia is a Salvadoran-American multimedia artist with a tenuous relationship to photography.

Indebted to a body of feminist, queer, decolonial, and poststructuralist scholarship, he remains a research-based artist, navigating process through texts and image archives. His work is interested in upending and intervening in how we define power, how it is represented, and importantly, how it is felt. He is an artist of mestizaje, pondering the ever-present hyphenation inherent in local (Molina-Garcia) and collective (Salvadoran-American) identity.

He holds an MFA degree in Photography from the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), and graduated with a BFA in Photography and a BA in Art History from the University of North Texas. Recent exhibitions include “Cut-Ups: Queer Collage Practices” at the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in 2016, and its previous sister iteration, “Cock-Paper-Scissors” at the ONE Archives gallery in Los Angeles, California; both curated by the ONE Archives Foundation.

He is the recipient of the 2017 Mind the Gap microgrant from the Art Tooth organization and the 2014 Jack Kent Cooke Graduate Arts Award, and has been awarded various other project and developmental grants.

He currently lives and works in Dallas, Texas.

DRP: Hello Jonathan, tell me where you are from.

JMG: Hi Raul! I was born in Apopa, a city close to the capital of El Salvador. I immigrated when I was six, and grew up in Arlington, TX up until I started college.

DRP: How would you describe the kind of photographic work would you say you do?

JMG: My work is deeply photographic, but generally speaking I am a lot more interested in processes of image assembly. My projects have most often used collage and montage-based processes, methods involving cutting, stitching, gluing the photo object. My arrival to photography came by way of literally “taking” images (out of magazines and printed matter, and later out of almost exclusively digital domains, like tumblr and other image archives). Only later did I touch a camera. Casting what I do as “image assembly” is a way for me to denote something a lot grander that the photograph achieves, in the way it constructs meaning and the photographer’s ability to compose, edit, and erase that significance.

So by way of interacting with photographic media by altering it, my trajectory as a photographer has involved teasing out the physicality of photographic technologies, and that desire perhaps accounts for the promiscuity of my practice - the way I’ve moved across different formats and devices.

DRP: The particular images we're sharing today work a lot like a documentary project. They follow a group of construction workers amidst their day labor; painting, roofing, and working seemingly in well established neighborhoods. Could you talk about this work?

JMG: Yes, it’s interesting that we would bring up this project in the context of how I work as a photographer, and you’re right to point out that it works “like” a documentary project, but maybe not completely. It’s a small set of images, I switch between color and B&W film. The Odessa images include a fair amount of abstraction, but “portraits” in the more conventional sense of the word are far and few in between.

DRP: Did you know any of the workers prior to taking these images?

JMG: I knew quite a few of the roofers before I started. There were two I didn’t know, and they don’t appear in the project as it currently stands. That wasn’t totally deliberate. One of them told me he didn’t want to be included, and I was too shy to approach the other, whom I harbored a little bit of a crush on. I knew the others - Danny, Flaco, Bocho, and Choncho - from working with my brother, Elmer. Shortly after I dropped out of my first year of college in New York, I returned home - unemployed - and sought out Elmer’s help. I worked with them for three months to save money before I started school in Denton. So the project picks up a few years after that first term of employment.

DRP: Were you surprised by anything while covering the laborers and their environment?

JMG: The interesting thing about this environment is that though it is populated by a Latino workforce, it is not, in fact, a body composed of undocumented Latinos. Perhaps this deserves emphasis, particularly now when the relentless racism and xenophobia in our political climate erases and flattens so much difference. Latinos are a patchwork, legally-speaking. We come with green cards, with full-on citizenship, with complicated statuses, and nothing at all.

This plays out in the construction industry all the time, where brown people of different citizenship status regularly work alongside each other.

So the frequently cited line that immigrants “take” jobs really reveals the fractures we have in our conception of latino labor - which is usually targeted as being the subject that is doing the taking - and of how we conceive of citizenship. Meaning, the conferment of citizenship has less to do with the immigrant’s place of origin or foreignness, and more to do with the immigrant’s color, assimilation, and language abilities.

As a real world example of this playing out in daily life, people are sometimes very surprised that I came to the United States illegally, a “coming-out” that says a lot about the class and social assimilation I’ve gone through as a DREAMER, and the sort of spaces I’ve been granted access to.

DRP: When you created these images, where you trying to convey or inform anything in particular?

JMG: The most impressionable experience of working construction is probably the vision and proximity it affords you. As a painter, you see the skeleton of a home, and you’re on the ground. As a roofer, you have a bird’s eye view, and the taller the home, the greater the perspective (and distance) becomes.

That’s a really important spatial and body orientation because it reproduces a very familiar labor disparity that exists between the people who work indoors versus the people who work outside. The painters here would fall in the first category, and the roofers are in the second. I can say that it’s a complicated experience - with a lot of ambiguity and loaded history - but certainly it is deeply felt. Down to the body - the way roofing as a profession wears heavy on the skin, sagging and browning from so much sun exposure.

So I suppose one of the most striking things about revisiting this work is considering how those two different physical positions carry into a visual language.

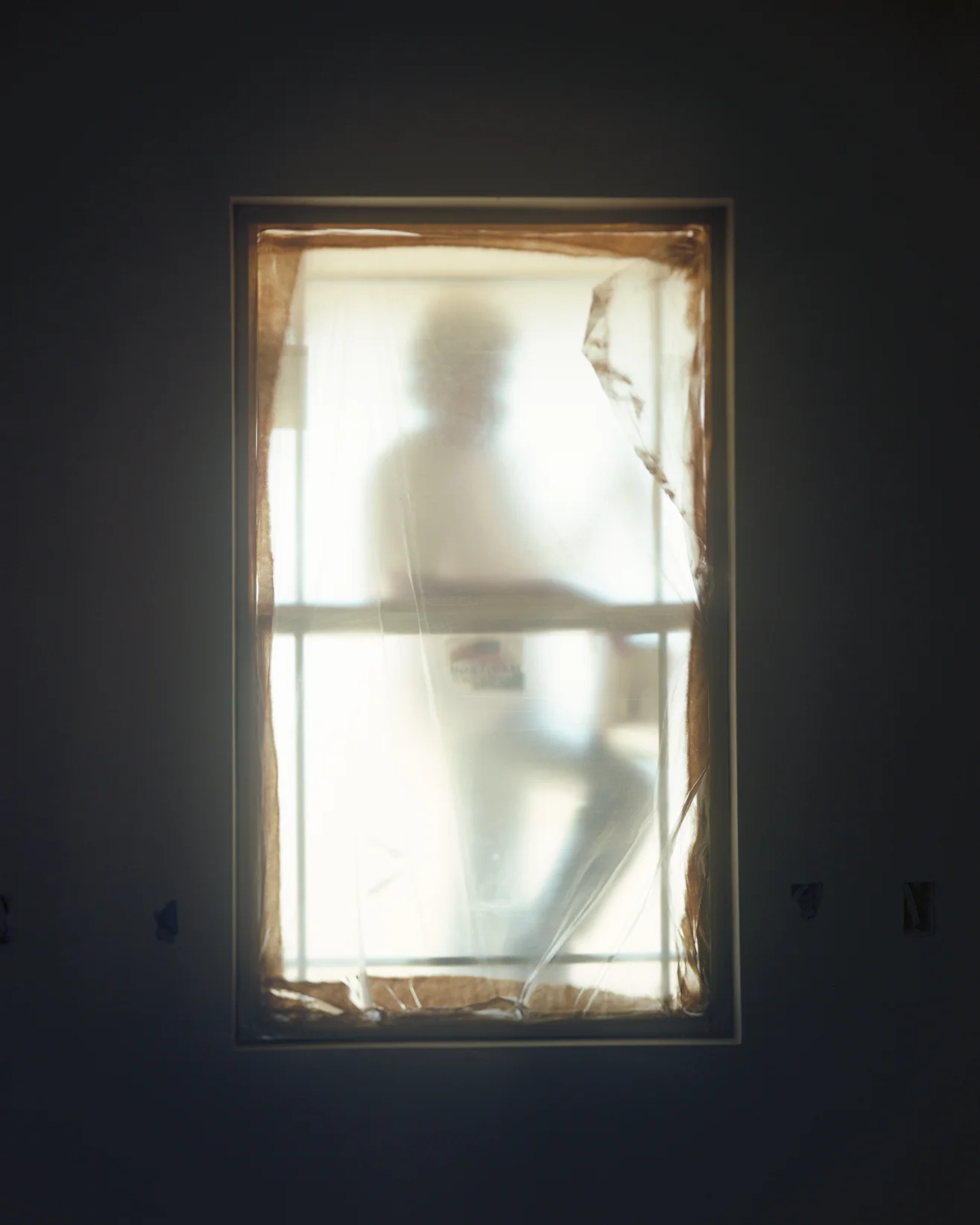

What happens in the photographs is that people frequently come in and out of concealment and often those shifts are also accompanied by a change in proximity to the camera. Danny, for example, is cloaked in shadows in the image above – the only one addressing the camera - and then appears out of them in the image below.

JMG: Iconographically, the Lencho Painting photograph is one of my favorites, for the way it most closely resembles all that i feel about the opacity of the brown body. That photograph is my way of asking questions about the stages of invisibility and visibility that we pass through. At what moments are we hidden and out of sight, and where/when are we revealed.

DRP: Does this series of works inform any work you are currently pursuing? Why or why not?

JMG: Completely, although there's a lot missing in the chronology of the Roofers and Painters project and what I'm doing now, and that leap is largely out of the different political consciousness that we now inhabit and the different work I’ve made since.

The roofers project for me always left off with a few open-ended questions; how does the queer identity of the photographer affect the development of a project about a mostly male Latino culture? Are my photographs queer? Are erotics present?

Without my pointed address, I feel this is a level of intersectionality that remains just under the surface, or too easily excluded from a broad survey of the photographs.

But my questions about the phenomenology of immigrant life is all-consuming now. And I can’t stop thinking about the spotlight on DREAMERS, the way we seem to be getting shepherded into assuming this country’s idealism about what and who the immigrant should be.

Right now I’m trying to build a mechanical camouflage suit that can be worn to aid border-crossers. The design involves sourcing images from Big Bend National Park, and printing photographic reproductions unto the suit that are altered through a motorized rotation. It’s a heavy technical project. I’ve been given a tremendous helping hand in the form of a microgrant by the folks at Art Tooth, so look forward to seeing that soon!

The difference between the two projects is obvious (and possibly staggering), but the suit is just a way to hybridize some lines of thought about how I’ve been dealing with photographic technologies and the body.

DRP: We are definitely looking forward to the fruiting of your work Jonathan. Thank you for the talk. Good luck with the project!

View more of Jonathan Molina-Garcia's work on his website here.